How to Design Organizations where Everyone Thrives

Did you catch the latest installment in our new expert interview livestream series, Leading with Every Action? We’re interviewing partner agencies and consultants, along with other experts, on a wide range of topics near and dear to leaders across our sector. Our goal with these livestreams is to offer thought leadership and spark vibrant discussion. For more expert discussions like these, join us on YouTube, turn on notifications, and never miss a stream.

Our friend Minal Bopaiah of Brevity & Wit joined us for the third livestream in our 3 part series around equitable and inclusive leadership. Check out our past stream recordings on YouTube, and read on for a brief excerpt from her book, Equity: How to Design Organizations where Everyone Thrives.

The first designer I heard talk about the intersection of systems and design was Antoinette Carroll, founder and president of the Creative Reaction Lab, a nonprofit organization that helps design healthy and equitable communities. In an illuminating TED Talk, she says, “When I shifted my understanding of design from object-making to systems-building, I began to realize that systems such as discrimination, racism, sexism, and even poverty were designed by people that made intentional choices around exclusion.”4 Carroll’s work—an inspiration for many designers, including yours truly—is centered around the fundamental truth that “systems of oppression, inequalities, and inequities are by design. Therefore, only intentional design can dismantle them.”5

When we confront the fact that the Founding Fathers designed a system that benefited White men who owned property above all others, we begin to see the legacy of that design in our institutions, governance systems, and organizations. To be fair, designing for inequity isn’t an American invention (although the United States did take it to another level, inspiring the Nazis to study US society so they could figure out how to codify violence and oppression for monetary gain and genocidal outcomes).6 From European colonialism to India’s Vedic caste system, designing for inequity appeals universally to those who are threatened—whether consciously or unconsciously—by the idea of sharing power with others.

Our country’s saving grace—and the saving grace of many nations—is the values enshrined in the living documents governing our society. Values like equality, justice, life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, freedom, and democracy have allowed generations upon generations of Americans—as well as people of other nations guided by their own intrinsic values of fairness—to iterate the design of their societies. When we dig into these values, we can redesign our educational and immigration systems—two systems that are interdependent—so that they produce equitable out- comes. That would mean that residents in the United States would have access to quality education regardless of their zip code and that immigrants would no longer be used as straw men in anti-Black rhetoric to justify oppression and disenfranchisement. We would begin to understand how systems, not just individual effort, lead to certain outcomes for individuals and groups.

With that understanding, just as we have designed for inequity, we can begin to design for equity.

Why Equity, Not Equality?

America’s founding documents enshrine equality, so why I am focusing on equity?

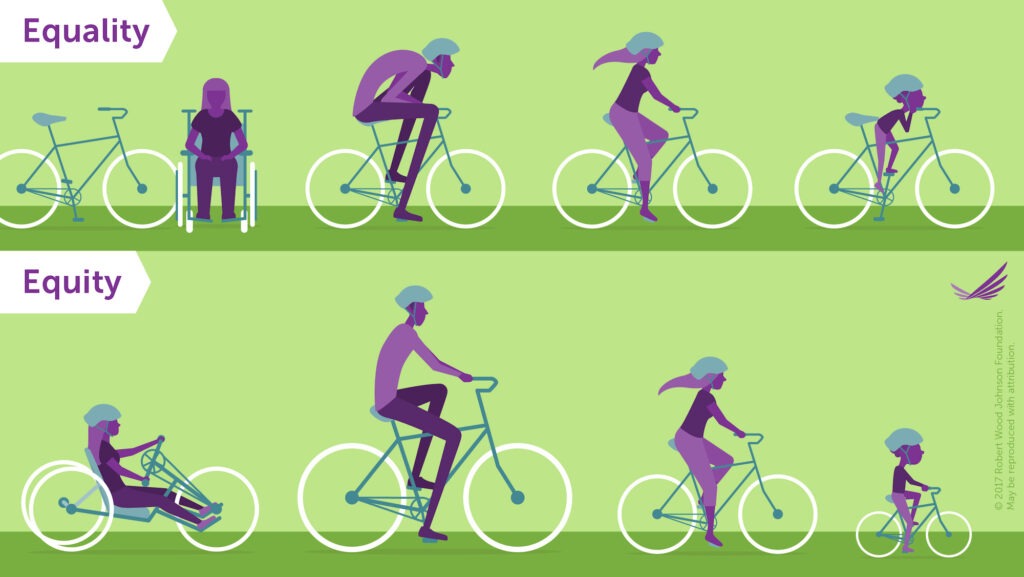

First, let’s unpack the difference between these terms. As a writer, I love words, but as the leader of a design firm, I admit that images sometimes convey complex concepts more powerfully. Figure 1, created by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, beautifully illustrates the difference between equality and equity.

Equality is when everyone has the same thing. Equity is when everyone has what they need to thrive and participate fully. Equity does not fault people for being different; it makes room for difference and then leverages it. In other words, equitable cultures, systems, and organizations are designed so everyone in the system has an equal chance to thrive. By thrive, I mean they have an equal chance to do work that fulfills them, live life authentically, and contribute their strengths to the community, organization, or culture of which they are a part.

This does not mean equality is bad. Sometimes equality is the appropriate response; in the movement for marriage equality, for example, “separate but equal” solutions like civil unions tip the scales in favor of injustice and second-class status for LGBTQ+ Americans. Only marriage equality could bring LGBTQ+ Americans the rights they deserve. But in other instances, equitable solutions, which allow for different approaches based on different needs, are sometimes ideal.

Equity has always been the middle child in the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) space, the concept we all acknowledge is important but often hop over to address feelings of inclusion. And I get why: focusing on feelings is an easier and better way to promote DEI. Equity is more about strategy and systems, concepts that can make people’s heads hurt. Personally, however, I care much more about equity than inclusion. Both are important, but the former drives the latter. Inclusion without equity is toothless; organizations end up talking about how to make people “feel more included” without doing the hard systems redesign that actually yields equal pay, more diverse leadership teams, and other signs of equal access to opportunity.

KEY DEFINITIONS

For those who are unfamiliar with DEI, here is how I define inclusion, diversity, and equity. I am also passionate about incorporating accessibility into my work, which allows me to use the acronym IDEA.

Inclusion is a dynamic state where individuals and groups feel safe, respected, engaged, motivated, and valued for who they are and for their contributions to organizational and societal goals.7

Diversity refers to the differences—both visible and invisible—within a group or among groups of people. They can include differences in gender, gender identity, ethnicity, race, native or Indigenous origins, age, generation, sexual orientation, culture, religion, belief systems, marital status, parental status, socioeconomic status, appearance, language and accent, disability, mental health, education, geography, nationality, work style, work experience, job role and function, thinking style, and personality type. It’s important to note that while a group can be diverse, an individual is not “diverse.”

Equity, in its simplest terms, means fairness. In an equitable society, all people have full and unbiased access to livelihood, education, participation in the political and cultural community, and other societal benefits.

Accessibility refers to the design of environments, products, devices, and services so that people of various abilities can use them with ease. Accessibility refuses to fault individuals for the ways in which they are different and instead emphasizes the rights of individuals with differences to be full and participating members of society.

Originally from English law, the concept of equity was developed to “supplement, aid, or override common and statute law in order to protect rights and enforce duties fixed by substantive law.”8 In other words, it allowed societies to live the spirit of the law rather than the letter of the law. The legal concept of equity recognizes that people with power must use discretion when meting out legal decisions to ensure fairness.

Equity in the workplace is about designing a system, a culture, or an organization so that everyone has an equal shot, however they may define what they are shooting for (success, happiness, work-life balance, etc.). It’s not about socialism versus capitalism or communalism versus independence. Rather, equity recognizes our interdependence and uses our collective power to create an environment where we all thrive and contribute our strengths. Moreover, equity gets us out of the hard work of constantly going against the system by creating a system that makes it easy to opt in to inclusive and equitable behaviors. Instead of looking for women to promote, for example, equity builds a system where women’s needs are centered; thereby, having women in positions of leadership becomes logical and natural. (A more detailed discussion of gender equity follows in chapter 1.)

To be clear, I am not calling for the design of an idealistic utopia. To paraphrase a Buddhist expression, the world is strewn with rocks and thorns; trying to carpet it all is a fool’s errand. I am intimately aware that life is inherently unfair; even if we were to solve all human-made injustices in the world, people would still die tragically and develop incurable diseases. By the end, life breaks everyone’s heart.

However, amid such unfairness and heartbreak, I believe that the greatest expression of our humanity is the creation of fairness. In my mind, it rivals the creation of beauty and the expression of truth, which have been human pursuits since we were drawing on the inside of caves. Equity is how our human soul resists the temptation of revenge born of grief and sorrow. It is a virtue that leads us to a higher expression of our true nature. It’s how we embrace interdependence so that we can design systems that work as well for others as they do for ourselves.